Mexico’s First-Ever Judicial Elections: What US Observers Should Know

On June 1, 2025, Mexico will elect judges for the first time - an unprecedented move that will reshape its justice system. Here’s why it matters, in Mexico and beyond.

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF):1

On Sunday, June 1, Mexicans will take to the polls to vote in the country’s first-ever judicial elections. 881 federal positions are up for a vote, with nearly 3,400 candidates participating in the election. There will also be state-level judicial elections across 17 states.

The judicial elections are problematic, to say the least. Not only does the popular election of judges politicize the courts, but it also threatens the rule of law and raises serious concerns about democratic backsliding. For the US, these changes pose significant risks to trade relations under USMCA, investor confidence in Mexico’s nearshoring potential, and bilateral cooperation on security and migration. The judicial elections underscore how Mexico’s domestic political shifts have direct and profound implications across the border.

Context of the Judicial Elections

The judicial reform traces its roots back to the presidency of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), whose relationship with the judicial branch was tenuous at best, particularly towards the end of his sexenio (six-year presidential term). AMLO has a long and convoluted history with Mexico’s federal electoral body and judicial branch, dating back to his loss in the highly contested and allegedly fraudulent 2006 presidential election and his subsequent defeat in the 2012 presidential election.

Much of the Morena movement is based on the strategic use of rhetoric and symbology to revamp and repackage the national narrative, history, and legacy for the purposes of political gains. The rhetoric behind the judicial elections is no different. Throughout his term, AMLO accused the Supreme Court and, more broadly, Mexico’s judicial branch, of corruption and in the service of Mexico’s elite interests. In the four months between Claudia Sheinbaum’s victory and the end of his term, AMLO wielded significant power, even as a lame duck, thanks to Morena’s sweeping victory at the polls, securing not only the presidency, but a super majority in both Chambers of Congress, all but ensuring the passage of some of AMLO’s most significant and controversial reforms – including the judicial branch elections.

Many analysts argue that it was the Supreme Court’s opposition to several policies central to AMLO’s presidency and Morena’s party platform that sparked the ire of the former president and motivated the judicial reform. The Supreme Court ruled the following (all policy proposals central to the AMLO administration) unconstitutional: the reform to militarize Mexico’s National police, the reform to the electricity law, and “Plan B” which targeted the National Electoral Institute (INE) through a reduction in both powers and budget. Unsurprisingly, “Plan B” was preceded by “Plan A” – a constitutional reform to weaken the independence of electoral institutions via constitutional change. This ultimately did not pass in Congress. “Plan C” entails the popular election of Mexico’s judges, which passed in the national Senate and 17 state legislatures in September 2024.2 Keeping with the tradition of utilizing national mythology to promote political causes, AMLO published the reform in the Official Journal of the Federation (DOF) on Independence Day in 2024.

Mexico’s Judicial Landscape and the 2024 Judicial Reform

Mexico’s federal judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, Circuit Courts, and District Courts. Each of Mexico’s 32 federal entities (which includes 31 states, plus Mexico City) has their own local court systems, as stipulated by the state constitution.

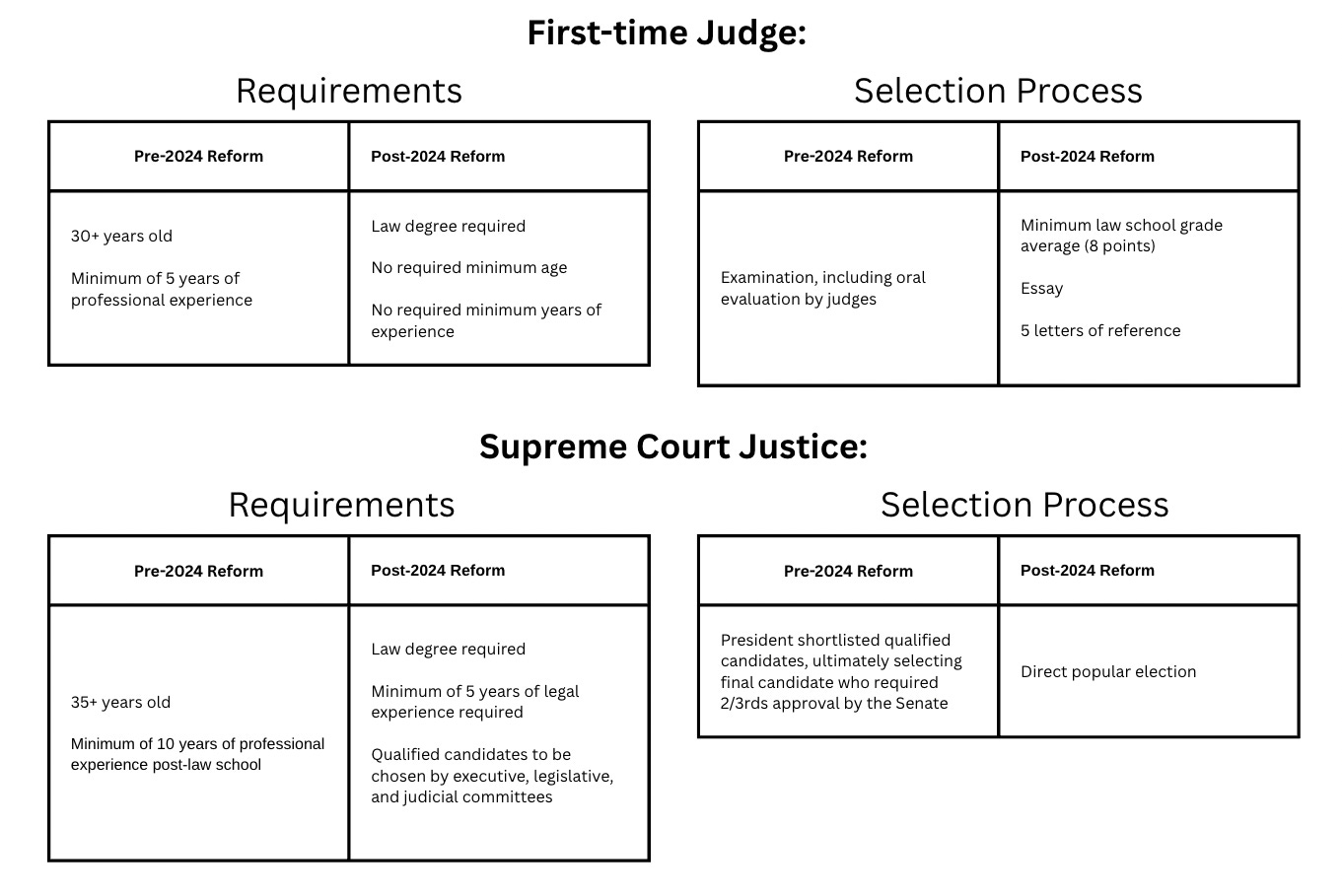

The 2024 judicial reform reduced the number of Supreme Court Justices from 11 to 9, reduced their terms from 15 to 12 years, and terminated case hearing panels. Most controversial in the reform, however, is the popular election requirement. Whereas Supreme Court justices were previously shortlisted by the President and then confirmed by the Senate, Supreme Court justices will now be elected via popular vote. The terms of current Supreme Court justices conclude on August 30, 2025, but eight of the current 11 justices have resigned from the Court in protest over the reform.3

What positions are up for election?

3,396 candidates are competing in the elections for 881 positions in the federal judicial system in 2025. There will also be judicial elections in 19 states, with an estimated 2,000 positions to be elected.4 5 Only half of Mexico’s judicial branch positions are up for election this year. The remaining positions will be elected in 2027.

How are candidates selected?

Tens of thousands of aspirants submitted applications for the judicial elections. Qualifying applications were then reviewed by evaluation committees from the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. However, the judicial branch evaluation committee resigned from the process in January after a court ruling ordered the suspension of the judicial election. As a result, the candidate list was sent to the Senate, but without review or approval from the judicial committee. In necessary cases, the Senate utilized a lottery system to select the candidates ultimately included on the list.

What is the campaign process?

Unlike traditional electoral campaigns in Mexico, campaigns for the judicial branch elections must be self-financed, meaning that candidates cannot accept public or private campaign financing. Moreover, though candidates will be granted airtime on Mexico’s radio and television systems, they cannot receive endorsements from political parties or elected officials. Unsurprisingly, social media has played an important role in the campaign process, with candidates participating in TikTok trends and Instagram Lives with the hopes of drumming up support among voters. Expectations for voter turnout are low, however. The INE estimates voter turnout to be between 8 and 20%, and that only half of the polling stations from the 2024 electoral cycle to be in use.6 7

What are the concerns and implications?

Throughout his presidential term, and with increased frequency in the final years, AMLO sustained allegations of corruption within Mexico’s judicial branch, and in particular, the Supreme Court. He argued that the current system made the courts accountable to Mexico’s richest and most powerful and that imposing popular elections would encourage accountability to the people – a common refrain in the populist rhetoric he rampantly employed throughout his term, and that his party, and successor, have fully embraced and consistently reiterated.

There has been consistent concern about the judicial branch elections, both within Mexico and abroad, from government officials to the markets. In November, Moody’s downgraded Mexico’s credit outlook to negative from stable in response to the passage of the judicial reform and burgeoning government debt.8

For the US, there is particular concern about what the judicial reform means for the future of the USMCA, particularly in terms of adjudicating trade disputes and ensuring the enforcement of the agreement’s labor mechanisms. The judicial elections call into question investment certainty in Mexico, posing a real threat to nearshoring and allyshoring in Mexico. A weakened judicial system has the potential to undermine cross-border cooperation on a variety of fronts, including security, migration, and drug flows. Mexico’s judicial elections are a clear reminder that domestic political developments can have direct implications across the border.

Within Mexico, it appears that there has been a shift in public support for the judicial elections. Despite the mass protests that the passage of the judicial reform provoked, 66% of Mexicans now approve of the popular election of the judicial branch.9

The judicial reform and upcoming judicial elections call into question the future of democracy in Mexico. These elections fundamentally politicize Mexico’s judiciary, making it inextricably linked to partisan politics. The popular election of Mexico’s judges weakens the country’s system of checks and balances and raises very significant concerns about clientelism and to whom, in actuality, the judges will be accountable. In a country where corruption and impunity are significant challenges and cartel-related violence is a pressing concern, ensuring transparency, functionality, and independence of the judicial branch, both at the state and federal levels, is essential.

But perhaps most concerningly, however, the popular election of judges is a serious threat to the rule of law in Mexico. For a country that experienced 71 years of uninterrupted rule by the PRI and opened up to democracy only 25 years ago, the decision to implement this policy, one that threatens rule of law with the potential to open the floodgates to democratic backsliding,10 presents a significant challenge for a country’s whose democratic tradition is less than three decades old.

“Moments in Mexico” will now include BLUF at the start of each piece, as inspired by my dear friend and mentor,

ofAnd spearheaded by some of the very leaders of the democratic opening movement, including AMLO himself

Thank you for this incredibly well-researched article about judicial reform. As predicted, voter turn-out was extremely low this past weekend. I heard stories of people voting based on factors like "vote for whoever has a Ph.D." instead of understanding what each candidate brings to the table as a whole (experience, not just credentials). But with a pool of thousands of candidates from which to choose, how can we voters possibly be well-informed enough to make the right selections? It's a lot of power to put in the hands of people who may not really know what's best.

🥲💕